by Brigitte van der Sande

An artist makes the world her world. An artist makes her world the world. For a little while. For as long as it takes to look at or listen to or watch or read the work of art. Like a crystal, the work of art seems to contain the whole, and to imply eternity. And yet all it is is an explorer’s sketch-map. A chart of shorelines on a foggy coast.

Ursula K. Le Guin, World-Making (1981), Dancing at the Edge of the World: Thoughts on Words, Women, Places, 1989, p. 47

For me, Bie Michels is a world-maker in the truest sense of the word. Her world has fluid contours, moving between object and subject, human and non-human, body and space, here and there, past, present, and future.

In Piles of Bricks 4, a site-specific installation with 5000 bricks and a performance that Michels created for the exhibition Spectres from Beyond during Other Futures Festival 2021 at the Brakke Grond in Amsterdam, the construction of bricks followed the contours, height and width of the artist’s body. She used brick dust to paint her figure as a mould and counter-mould, and for flying and floating bodies that defy the gravity of their source material. During the performance, Michels, appearing live in Amsterdam, and the Malagasy artist Liantsoa Rakotonaivo (Li), shown in a pre-recorded video in Madagascar, follow the same plan of action, called ‘scores’, but from different perspectives; hers in the context of conceptual and performance art in the West, his as a dancer/choreographer in an art installation of his own in the brickmaking manufactory on the island. Michels doesn’t try to bridge the gap between their cultures, geographies and contexts; on the contrary, she acknowledges the different situations and positions that they each are working in.

Their connection has grown during the years they have worked together, starting from her first visit to Madagascar in 2014 and continuing to this day. Michels understands the complexities of this collaboration, but is nonetheless pleased to hear Li – who makes bikes for a living – say that working together has decolonized his mind. In the 3-channel video installation La couleur de la brique (2017) Li and other artists perform among the brickmakers, who are proud of their craftmanship; it connects them to an ancestral tradition.

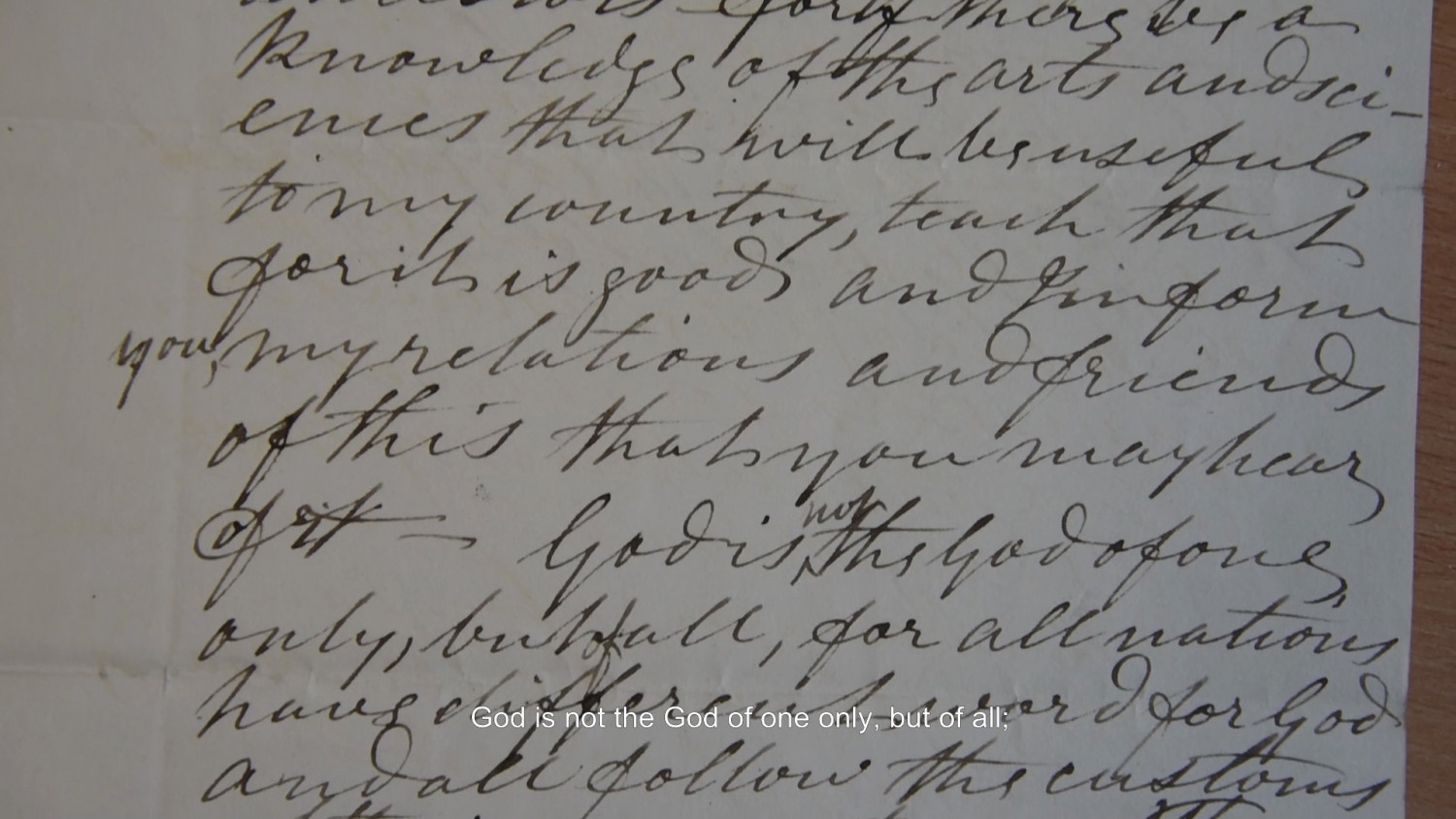

The extraordinarily close and mutually beneficial relationship between the Scottish missionary ‘engineer’ James Cameron and the powerful Queen Ranavalona I in the 19th century in Madagascar is the starting point for Ingaby Kama, a film that Michels made in 2017-2018. The balancing act between two cultures becomes apparent through the correspondence between members of the London Missionary Society and the missionary, and between Cameron and the queen. Michels returns the letters kept in the archives of the Church Mission Society in the UK and takes them to the island in the form of copies, where a number of Malagasy people read them aloud, joined by the voice of a Scotsman. To my mind, their reading of this correspondence written in the language of the foreigner, overlaid by a heavy Madagasikara/French accent, causes friction. As the Senegalese philosopher Felwin Sarr points out, it may be necessary to revitalize African languages in order for people to detach themselves from the ideological system behind the language of the invader/colonizer. Re-owning the letters, however, may be one of the many steps in the decolonialization of minds and collective imaginaries. The sovereignty of the proud queen rings loud and clear through the foreign language.

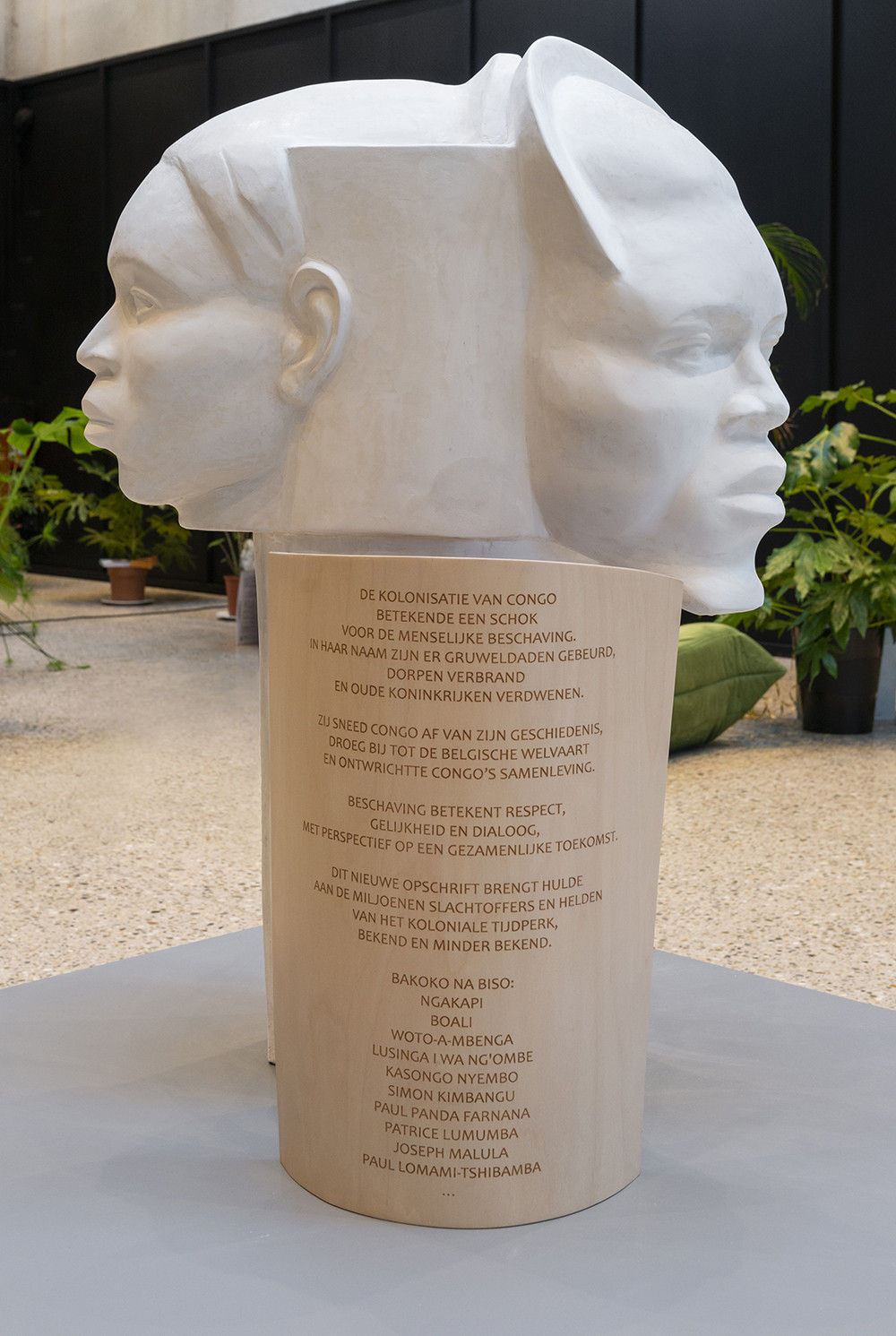

Bie Michels was born and raised in Kimweza, Congo, and Lovanium, the first university in the Belgian colony. Living in a house on the modernist-style campus, Michels grew up in the bubble of a Belgian culture that was rarely penetrated by the Congolese reality outside. These experiences made her sensitive to her position as a white woman and feminist artist in a world that managed to stay white and male-dominated till recent years, when the walls started to be knocked down by women, Black, Indigenous and People of Colour – step by step and with subtle or open resistance from the people in power, as Michels shows in her film (Pas) Mon Pays, Part I and II (2019) and the installation The Copy (2019), which also figures in the film. Here, together with a group of Belgians with Congolese roots in the city of Mechelen, Michels discusses an alternative inscription for a colonial monument. As it turns out later, while Michels is in the process of making the film, the Mayor of Mechelen, Bart Somers, commissions the historian Marnix Beyen from the University of Antwerp to provide a reference to the atrocities of the colonial regime. A thoughtful gesture?

No, as the group in Mechelen in Part I of the film and the many Congolese interviewed by Michels during her visit to Congo in Part II articulately explain. Somers – who was awarded the World Mayor Prize in 2016 for his inclusive policy – welcomes the initiators at City Hall and, after 30 minutes, mansplains to Michels that the discussion has already moved from an intellectual to an emotional level and turns down their reasonable arguments for participation. It’s clear: letting go of patriarchal and colonial attitudes is hard. A discussion needs to be sparked about the colonizer’s persistent role in erasing the history and civilization of the colonized country, and not just in Belgium. Only by learning about her ancestors and the history of her country can she change the future, says Merveille Yabunde, a young history student at UNIKIN (formerly Lovanium) in her interview for the film. Then she immediately and humorously confronts the cameraman about the lack of camerawomen in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, as it is now called. Michels alternates footage of the interviews with images of her visit to her childhood home. Congo is part of Michels’ history, just as Belgium is, and like every migrant she feels a bond with both, but will never fully belong to either.

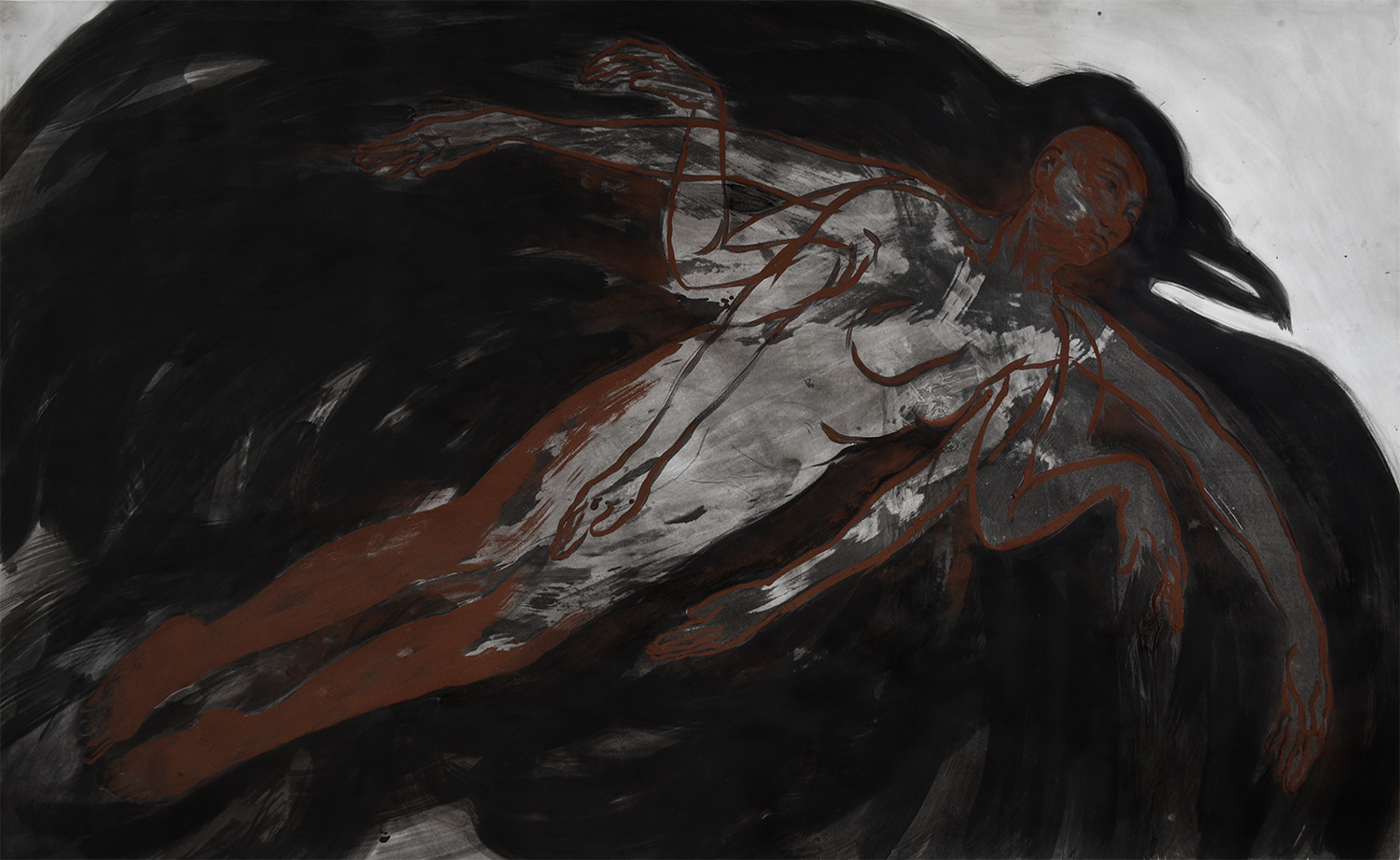

This position of inbetweenness is a great advantage to an artist who moves from discipline to discipline as if there are no borders. Although I had been aware of her mastery of installation and performance art and filmmaking, I was blown away by her command of painting when she invited me to her studio in 2021 and when I saw other paintings later. The woman-bird works, explorations of hybrid and mythical creatures that are born before our very eyes, painted in multiple thin layers of India ink and brick dust, interest me in particular. In one of her recent paintings a woman soars through the air with the shadow of a raven behind her, like a cloak protecting her. This most intelligent of birds has the ambiguous reputation of being the bringer of both good and bad luck and is a symbol of transformation. The fact that ravens not only use tools but also make them puts these birds in the realm of world-makers. In her work, Bie Michels explores all kinds of worlds to make a new world – one with sketchy boundaries, but a world to be immersed in.

To end with a quote by the same science fiction writer as at the beginning: “To make a new world you start with an old one, certainly. To find a world, maybe you have to have lost one. Maybe you have to be lost. The dance of renewal, the dance that made the world, was always danced here at the edge of things, on the brink, on the foggy coast.”

March 2023